What Are Some Ways Ancient Egyptian Kings Asserted Their Legitimacy in Their Art

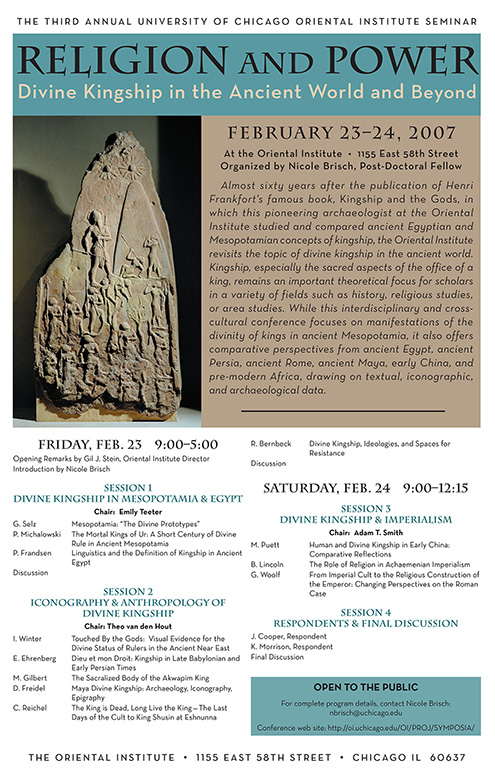

Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Across

Organized by Nicole Brisch

The Oriental Institute of the Academy of Chicago

1155 East 58th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

February 23–24, 2007

- The aim of the symposium

- Contact

- References

- Abstracts and Bios

- Conference Program (PDF)

- Practical information

Kingship, especially the sacred aspects of the office of a king, has for a long time fascinated scholars in a variety of fields such every bit history, religious studies, or area studies. Kingship (or whatever kind of absolutist power) and its close relationship to and apply of religion for the purpose of legitimizing power seem an near universal concept in human history. Frazer's famous work The Golden Bough: A Study in Religion and Magic has been highly influential on the topic of sacred or divine kingship and continues to be then until today (due east.g. Quigley 2005).

The application of Frazer's report to the civilizations of the ancient Near East is, notwithstanding, problematical. His interpretation of sacred kingship was strongly influenced by Christian imagery (Feeley-Harnick 1985). Frazer fabricated a sure form of regicide in which the divine king is sacrificed to ensure connected fertility and prosperity for the community a central element of divine kingship. This class of regicide, even so, does not seem to play an of import role in all of the societies that exhibit the miracle of divinization of the king.

Among the primeval civilizations that showroom the miracle of divinized kings are early on Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. Therefore it is all the more surprising that aboriginal Egyptian-to a lesser extent-and aboriginal Mesopotamian kingship are often ignored in comparative studies of the phenomenon of divine or sacred kingship.

Mesopotamia

The first Mesopotamian ruler who declared himself divine was Naram-Sin of Akkad. Naram-Sin reigned sometime during the 23rd century BCE just the exact dates and duration of his reign are still field of study to inquiry. According to his own inscription the people of the urban center of Akkad wished him to be the god of their urban center. This outset example of cocky-deification also coincides with the first earth empire of the rulers of Akkad, the starting time time that a dynasty established a territorial ruler over large parts of Mesopotamia. It was too accompanied by certain changes in religion, in which the king proliferated the cult of the Ishtar, the goddess of state of war and dear. Naram-Sin seems to take emphasized Ishtar in her war-similar attribute ('ashtar annunitum) and began to refer to himself as the hubby/warrior of Ishtar.

After Naram-Sin no ruler declared himself divine until about 200 years had passed, when Shulgi (2095–2049 BCE), the 2nd rex of the Third Dynasty of Ur, took up the custom of self-deification one time more. His self-deification may have been viewed in attempts to consolidate the empire he had inherited from his father. The cult of the divine ruler seems to have culminated under Shu-Sin, who was probably Shulgi's son or grandson and began an extensive program of cocky-worship (Brisch in press). Afterward Shu-Sin the divinization kings was abased again.

Whether the kings of the One-time Babylonian period (c. 2000–1595 BCE) can exist considered divine is still subject field to debate. Some consider the kings Rim-Sin of Larsa (1822–1763 BCE) and the famous Hammurabi of Babylon (1792–1750 BCE) to accept been divine. Both kings struggled to expand their area of influence, and therefore their self-deification may have been part of a strategy to consolidate and legitimize their powers.

The Briefing

While Egyptian kingship has been studied time and again (for example O'Connor and Silverman 1995; Gundlach and Weber 1992; Gundlach and Klug 2004) the terminal overarching study of religious aspects of ability in ancient Mesopotamia is almost sixty years onetime (Frankfort 1948). New materials have come to light since then that make a reconsideration of the topic essential not just to scholars of the ancient Almost East but also for scholars of other disciplines.

Agreement of the origins of Mesopotamian kingship is a key element for understanding the divinization of the male monarch. Recently, several, partly differing accounts of the origins of kingship in Mesopotamia have appeared (eastward.thou. Heimpel 1992; Selz 1998; Steinkeller 1999; Yoffee 2005).

Heimpel (1992) and Selz (1998) based their analyses mainly on a report of the semantics of the words for ruler and concluded that in the early third millennium BCE in that location were two forms of kingship, i that had its basis in sacred bureaucracy, and some other ane that was based on the dynastic principle. The dynastic principle then became prevalent with the rulers of Akkad. Steinkeller (1999) assumes that in early Mesopotamia kings drew their power from existence priests for female deities. After a male deities became more prominent in the pantheon a split of secular and sacred power took identify which led to the invention of the military leader who assumed secular power and became the male monarch. There is, nonetheless, no evidence for this reconstruction. Yoffee (2005) embedded his reconstruction of the primeval cities, states, and civilizations in the wider context of a critique of social (neo-)evolutionist theories. While the discussion of ability in these earliest cities and states figures as just i of several aspects of an ancient civilization to exist taken into consideration, he emphasized that the ancient Mesopotamian state consists of several parts that could do power, and that Mesopotamian history is therefore largely shaped by conflicts and struggles between these different entities. Mesopotamian kings are co-ordinate to him non all-powerful as their influence is sharply curbed by local powers and other institutions that sprang up when the fundamental power was weak.

Particularly important and thought provoking in connection with the topic of divine kingship are the works of Selz (1997; 2004) and Michalowski (e.g. 1988; 2004). According to Selz (1997) the introduction of divine kingship also presupposes the growing humanization of deities in ancient Mesopotamia. All the same, this assumption should be discussed in further item within the framework of this conference.

Another of import cistron is the iconography of the divine king. The near famous example of this is, of course, the Naram-Sin stela (Wintertime 1996). The stela depicts the rex as a super-homo being who wears attributes of kings as well as symbols of divinity, such equally the horned crown. In Mesopotamian iconography the horned crown and the flounced robe are both attributes of divinity, simply divine kings can only be depicted equally wearing either one, never both together (Boehmer 1957-1971). This indicates that in that location are subtle differences in the way divine kings and deities are represented. Peculiarly for Mesopotamia, but also for other areas in which divine kingship is attested, information technology would exist of import to accost further how iconography contributed to buttressing the ideological foundation of divine kingship.

Cantankerous-cultural comparisons correspond an important factor in the report of divine kingship in ancient civilizations. The areas that would lend themselves best for such a cross-cultural comparison would exist ancient Rome (east.g. Cost 1987), Africa (e.chiliad. Apter 1992; Gilbert 1994) and ancient China (Puett 2002), and Maya. These comparisons may help bridge gaps in the often highly eclectic evidence of ancient societies and open up new venues of inquiry that have not been pursued previously. There is besides a question whether similar preconditions produce similar political-ideological outcomes, and what the preconditions for such processes are. This volition provide insights into the more general question of the relationship between human political hierarchies and ideas about the supernatural.

The topic of divine kingship should be viewed in a broader context of the use of religion to legitimize ability in ancient states. The Achaemenid empire offers a new perspective for this line of research equally there is a rich historical and iconographic documentation (for example Lincoln forthcoming; Ehrenberg forthcoming).

Expectations

The cross-cultural and anthropological comparisons suggested in this symposium volition enhance our agreement of divine kingship as an important strategy of pre-modern rulers to bolster their power and to create new ideological foundations to support growing political expansionistic tendencies. The symposium will also further our noesis of ancient Mesopotamian and ancient Egyptian kingship, offer new insights into the human relationship of power and faith in pre-modern societies, and make ancient civilizations part of a discourse on kingship.

Key Participants

- Reinhard Bernbeck (Binghamton University, Virtually Eastern archæology)

- Erica Ehrenberg (NYAA, Art History)

- Paul Frandsen (Copenhagen Academy, Egyptology)

- David Freidel (Southern Methodist Academy, Maya)

- Michelle Gilbert (Sarah Lawrence College, Art History and Anthropology)

- Bruce Lincoln (University of Chicago, History of Religions)

- Piotr Michalowski (Academy of Michigan, Assyriology)

- Michael Puett (Harvard Academy, Chinese History)

- Clemens Reichel (University of Chicago, Near Eastern Archæology)

- Gebhard Selz (Academy of Vienna, Assyriology)

- Irene Winter (Harvard University, Art History)

- Greg Woolf (St Andrews Academy, Ancient Rome)

Discussants:

Kathleen Morrison (University of Chicago, Anthropology)

For data and free registration, contact:

Nicole Brisch (Organizer)

Post-Doctoral Fellow, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

1155 E. 58th St.

Chicago, IL 60637

Usa

nbrisch@uchicago.edu

Tel. due south(773) 702-3291

References

Apter, A. 1992. Blackness Critics and Kings: The Hermeneutics of Power in Yoruba Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Boehmer, R.M. 1957-1958. Götterdarstellungen in der Bildkunst. In Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie, ed. East. Weidner and W. von Soden, Bd. 3 Fabel – Gyges, pp. 466–469.

Brisch, N. in press. The Priestess and the King: The Divine Kingship of Shu-Sin of Ur. Journal of the American Oriental Society.

Ehrenberg, E. Forthcoming. Persian Conquerors, Babylonian Captivators.

Feeley-Harnik, Thousand. 1985. Issues of Divine Kingship. Annual Review of Anthropology 14: 273–313.

Frankfort, H. 1948. Kingship and the Gods. A Written report of Ancient Near Eastern Religion equally the Integration of Society and Nature. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Gilbert, M. 1994. Aesthetic Strategies: The Politics of a Purple Ritual. Africa 64: 99–125.

Gundlach, R. and Klug. A. (eds.). 2004. Das ägyptische Königtum im Spannungsfeld zwischen Innen- und Aussenpolitik im 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Gundlach, R. and Weber, H. 1992. Legitimation und Funktion des Herrschers: vom ägyptischen Pharao zum neuzeitlichen Diktator. Schriften der Mainzer Philosophischen Fakultätsgesellschaft Nr. 13. Stuttgart: F. Steiner.

Heimpel, W. 1992. Herrentum und Königtum im vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Alten Orient. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 82: 4–21.

Lincoln, B. Forthcoming. Faith, Empire, and Torture: The Case of Achaemenian Persia, with an appendix on Abu Ghraib. Academy of Chicago Press.

Michalowski, P. 1988. Divine Heroes and Historical Self-Representation: From Gilgamesh to Shulgi. Message of the Canadian Gild for Mesopotamian Studies xvi: nineteen–23.

———. 2004. The Ideological Foundations of the Ur III State. In 2000 five.Chr. Politische, wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Entwicklung im Zeichen einer Jahrtausendwende. iii. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 4.-seven. Apr 2000 in Frankfurt/Main und Marburg/Lahn, ed. J.-West. Meyer and W. Sommerfeld. CDOG 3, pp. 219–235. Saarbrücken: Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag.

O'Connor, D. and Silverman, D.P. (eds.). 1995. Ancient Egyptian Kingship. Leiden: Brill.

Cost, S.R.F. 1987. From Noble Funerals to Divine Cult. In Rituals of royalty: ability and ceremonial in traditional societies, ed. D. Cannadine and South.R.F. Price, pp. 56–105. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

Puett, M.J. 2002. To go a god: cosmology, cede, and cocky-divinization in early China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Quigley, D. (ed.). 2005. The Graphic symbol of Kingship. Oxford: Berg.

Selz, Chiliad. 1997. 'The Holy Drum, the Spear, and the Harp': Towards an Understanding of the Problems of Deification in Third Millennium Mesopotamia. In Sumerian Gods and Their Representations, ed. I.J. Finkel and M.J. Geller, pp. 167–209. Groningen: Styx.

———. 1998. Ueber mesopotamische Herrschaftskonzepte. Zu den Ursprüngen mesopotamischer Herrschaftsideologie im iii. Jahrtausend. In dubsar anta-men. Studien zur Altorientalistik. Festschrift für Willem H.Ph. Römer zur Vollendung seines seventy. Lebensjahres mit Beiträgen von Freunden, Schülern, und Kollegen, ed. M. Dietrich and O. Loretz, pp. 281–344. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

———. 2004. 'Wer sah je eine königliche Dynastie (für immer) in Führung?' Thronwechsel und gesellschaftlicher Wandel im frühen Mesopotamien als Nahtstelle von microstoria und longue durée. In Macht und Herrschaft. Veröffentlichungen des Arbeitskreises zur Erforschung der Religions- und Kulturgeschichte des Antiken Vorderen Orients und des Sonderforschungsbereiches 492, Bd. 5, ed. C. Sigrist, pp. 157–214. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Steinkeller, P. 1999. On Rulers, Priests, and Sacred Marriage: Tracing the Evolution of Early Sumerian Kingship. In Priests and Officials in the Ancient Near East. Papers of the Second Colloquium on the Ancient Most Eastward—The Urban center and its Life held at the Middle Eastern Culture Eye in Japan (Mitaka, Tokyo), ed. Yard. Watanabe, pp. 103–137. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Wintertime.

Winter, I. 1996. Sex, Rhetoric, and the Public Monument: The Alluring Body of Naram-Sîn of Agade. In Sexuality in Ancient Art. Near East, Egypt, Greece, and Italy, ed. N.B. Kampen, pp. 11–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yoffee, North. 2005. Myths of the Archaic State. Development of the Primeval Cities, States, and Civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing.

Source: https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/symposia/religion-and-power-divine-kingship-ancient-world-and-beyond-0

0 Response to "What Are Some Ways Ancient Egyptian Kings Asserted Their Legitimacy in Their Art"

Post a Comment